I do not believe that one should wholly or absolutely reject an ideal or philosophy just because its logical conclusion is wrong or unethical. However, we must understand and remind ourselves that all ideologies have logical conclusions that lead to immoral and unethical outcomes. This is true with the classical view of Utilitarianism. I believe that the Utilitarian ideals that Jeremy Bentham, and John Stuart Mill espoused are fine enough. However, “bioethicist” Peter Singer, took Utilitarian philosophy to its end conclusion, as demonstrated in his 19722 essay Famine, Affluence, and Morality (Link).

A quick summary of the essay more or less follows as “action is required when happiness is not being maximized/whenever suffering is occurring, and nothing of moral value will be lost”. Ignoring some of the finer points of what “maximizing happiness”, “reducing suffering”, or what is of “moral value”, my main concern is the issue of requiring action.

I am not a consequentialist. I do not believe in the ends of morality or ethics as the purpose of morality or ethics. I more or less believe that one should do something because it is the right thing to do, rather than because it will lead to a good outcome. As such, I do not believe that the “ends justify the means”.I also believe that, under the veil of ignorance principle (Rawls, A Theory of Justice), that I would want people to act in the same moral or ethical way that I act, because I would want them to treat me the same way I treat others (with fairness). With consequentialist philosophies such as Utilitarianism, action is required to be a moral or ethical person. This principle, known to those who argue against Utilitarianism, “Demandingness Objecttion” (Corbett).

The requirement of action is sticky in issues that do not have clear outcomes. Sometimes, more harm than good is done when a good moral action is done. Say you encounter a homeless person on the street, asking for some money in order to buy food for himself. Singer would argue that it is not a great sacrifice to give the man a few dollars. While this is objectively the morally correct thing to do, you may end up hurting the man overall if he is an abuser of drugs. While drug abuse is not as prevalent among the homeless as is stereotypically believed, unless you follow the man around, and inspect his use of the donation, there is no way of knowing whether or not you gave money to someone who will end up hurting themselves further. I am not arguing that we should not help homeless people. I am arguing that the morally correct solution that the Utilitarian approach to such situations are not as cut and dry as Singer believes them to be.

The next issue I have with Singer’s approach is who deserves the charity, and scalability. Singer discusses how giving charity to those in need is irrelevant to their distance or relation to you in regards to the situation of their poverty or suffering. Singer specifically discusses how a starving child in Bangladesh and a starving child in front of you have the same moral weight. I agree with this assessment. However, Singer more or less argues that because there is suffering somewhere on Earth, action is required to alleviate that suffering.

“If my argument so far has been sound, neither our distance from a preventable evil nor the number of other people who, in respect to that evil, are in the same situation as we are, lessens our obligation to mitigate or prevent that evil. I shall therefore take as established the principle I asserted earlier. As I have already said, I need to assert it only in its qualified form: if it is in our power to prevent something very bad from happening, without thereby sacrificing anything else morally significant, we ought, morally, to do it” (Singer).

Singer even discussed how the scalability of moral action can be overwhelming for an individual, in contrast to the overwhelming majority of people who could help, but do not. Much to Singer’s credit, he himself does a very good job living his principles, as he lives a relatively low level economic life, is a vegan, and more or less donates everything he can to those in need. I, however, do not believe that charity on its own can solve poverty in the long term, and the reasons for poverty exist because of systemic issues, such as geography, economic, cultural, or political reasons.

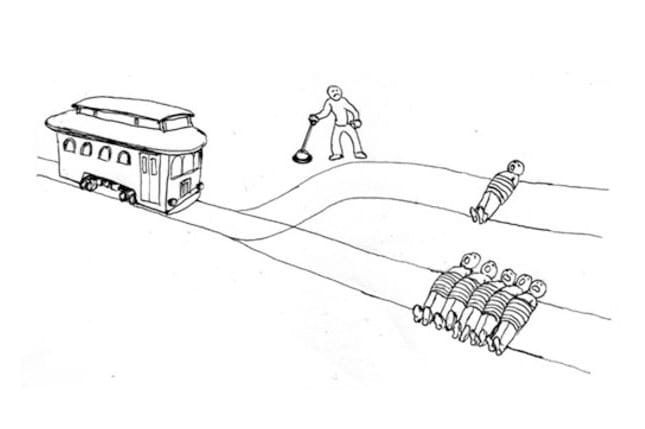

Furthermore, we live in a world of scarce and limited resources. I coupled together scalability and distribution of charity, because it is just not feasible to distribute the scarce resources of charity. Even ignoring the charity argument in general, consequentialist philosophy in general believes that one should seek out moral actions that have a good moral outcome. I do not believe this is the correct approach, as when you have situations where you have to make a moral choice, and someone ends up with damages, how do you morally decide who should have the damages? The classic example of this the trolley problem as seen above.

This is the core as to why I am not a Utilitarian specifically, and a consequentialist in general. I do not believe that unilaterally deciding who should or should not be treated ethically at the expense of others is ethical. I do not understand how making a decision that helps one, but harms another is considered ethical. The world is a complex place, and I do not see any reasonable situation where such a black and white dichotomy could exist. It is for this reason that I believe Utilitarianism is ultimately an unethical philosophy: it excuses evil actions with the excuse that the greater good, greatest happiness, or reduction of suffering has occurred. Again, ignoring what those phrases and terms mean specifically, I believe that evil means taint the end result.